FYI, this is a paper that I had to write for my history class — so if it sounds very professional, that’s because it is. I thought I should post it because I learned a lot about Highlife and especially Fela Kuti, and I dont want this to just be a Hip-Hop and R&B blog. So, anyways, on with the essay:

Question: How Did Afrobeat and Highlife Become the Soundtrack to De-colonial Africa?

Africa is considered the motherland of civilization: it is widely believed to be the origin point of humanity and the birthplace of advanced civilization. The ancient Egyptians were based in Africa, and they built one of the seven wonders of the Ancient world: the pyramids. Africa birthed empires, such as Kush and was also known as the breadbasket of the Persian and Roman Empires. It’s also widely regarded as one of the birthplaces of music with evidence of instruments being created and used via cave paintings dating back to 6000 BC. Fast forward to the late 19th century. The white men entered the continent and sought dominance over its inhabitants, colonizing all of Africa.

The African colonization process was called the “Scramble for Africa”, as countries like Spain, France, Britain, Portugal, Italy, and Germany wanted the continent’s natural resources, primarily minerals, rubber and food. By 1914 all of Africa except Liberia and Ethiopia was a colony of a European country. Then the first world war took place, and thousands of Africans were sent out into the front lines to fight for counties that they themselves despised. All in all, about 150 thousand Africans died in WWI. Furthermore, African nations were dealt as pawns between Europeans who won and lost the conflict. Then, after the second World War, many of these colonizer countries became further weakened, as they’d depleted their resources in this follow-up six year global war. Several African colonies used this opportunity to rebel against the weakening militaries to regain their independence. These initial revolutions were mostly successful, leading to the more – and thus the decolonization movement caught fire across the continent.

During the 1950s-70s, African decolonization was growing rapidly. After World War II, many European countries were forced to liberate their African colonies due to a lack of money and resources. But, just because these colonies were liberated did not mean that they didn’t have their fair share of issues. There were civil wars, a lack of natural resources, and poor education plaguing nations across Africa. So, in the midst of all this turmoil, activists rose up – and they used a form of expression that was birthed on the continent–music. Afrobeat and Highlife artists in Africa used their artistry to speak about social issues through their music. These two genres became the soundtrack of the de-colonial era.

Assertion 1: Highlife and Colonialism

Highlife was born as a direct result of colonialism. The musical style is a blend derived from mixing the jazz music Ghanaians overheard European soldiers playing in their barracks and in their bands with their own traditional Ghanaian music. Interestingly, when it was first performed in the early 20th century, Highlife was entirely inaccessible to anyone except white people. It was only played at expensive clubs that only Europeans, most likely the Brits that owned parts of Nigeria and Ghana, could afford. This is how Highlife got its name. It was, at its core, music for the colonizers by the colonized. But, there were still many great and beloved African highlife artists. There was E.T. Mensah, who was known as the “King of Highlife” and performed with Louis “Sachmo” Armstrong or Rex Lawson who toured all over Ghana and Nigeria with his “Mayor’s Band”. But these artists were exceptions – most highlife bands and artists were only made to provide the rich white man with music. That’s why many Africans hated the genre, noting that it didn’t represent their culture. Fela Kuti, the future create of Afrobeat, once said, “[Highlife] has nothing African in it”, and when discussing its origins, noted that it was probably a type of “pleasant noise that the white man listened to while drinking his beer and feeling he had a ‘high life.’ (Labinjoh, 1982). Highlife was the first step in this musical mixture. A precursor to the genre Kuti created and mastered: Afrobeat.

Assertion 2: Afrobeat: Music for the People

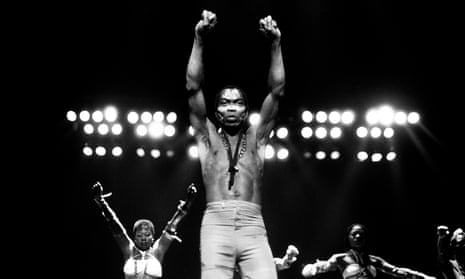

After the decolonization period gained serious traction, and more colonies were liberated, the main music of the moment morphed from Highlife into Afrobeat – a genre that spoke to the African people. Like Highlife before it, Afrobeat was fueled by western music, specifically jazz, but unlike Highlife, Afrobeat was all about politics and social issues. Africans were looking for their own identity post-colonialism – and so they used music to mold that identity. But the story of Afrobeat can be summed up by the story of its founder: Fela Kuti. Kuti was born and raised in Nigeria to a middle class family that was very interested in politics. His mom was a political activist while his dad was a reverend and school principal. Kuti learned how to play piano and percussion, later landing him a spot as the frontman in Highlife band Koola Lobitos, where he toured around the US in the late 60s. In Oakland, California, he witnessed the rise of the black panther movement and knew he wanted to infuse political messaging into his music. And, by the time he returned Africa really needed a man like Kuti. While he was gone, there was still a civil war in Nigeria, which ended with the military having total control over the country. People went hungry, and many lost their homes. Kuti knew that he had to stand up for what was right. So, when Kuti returned home, that is exactly what he did. His album Zombie is the first assault – it is solely focused on criticizing the Nigerian military and their actions against citizens. He calls them “Zombies” as they only follow orders and don’t think for themselves. Vivane Saleh-Hanna writes: “In Nigeria the repercussions of musical rebellion were also apparent. Fela faced much opposition and attack from the Nigerian military regimes during his life.” (Saleh-Hanna, 2008) So, his second assault was, and had to be more…complex.

When he first came back to Nigeria in 1970, Kuti bought a house that was the hub for his activism throughout the decade. This house was called Kalikuta Republic, which he declared an independent state. Author Alexander Stewat writes, in his Kuti biography Make It Funky: “His compound, the Kalakuta Republic (Swahili for “rascal”) for the cellblock where he had been confined, was fortified and expanded with the construction of his own recording studio.” (Stewart, 2019). Kalakuta Republic is where he recorded Zombie and many of his 1970s albums such as Gentlemen & Fear Not For Man. All of these albums took shots at the Nigerian government. Kuti, through the creation of these works, demonstrated that he was not afraid of what the powers that be might do to him in retaliation (“I am a man…I [will not] run, brothers and sisters”). Fela said about these albums: “Music is a weapon of the future / music is the weapon of the progressives / music is the weapon of the givers of life”. And, there is no other artist that used that weapon better than Fela Kuti.

Assertion 3: Will We Ever Escape Colonialism?

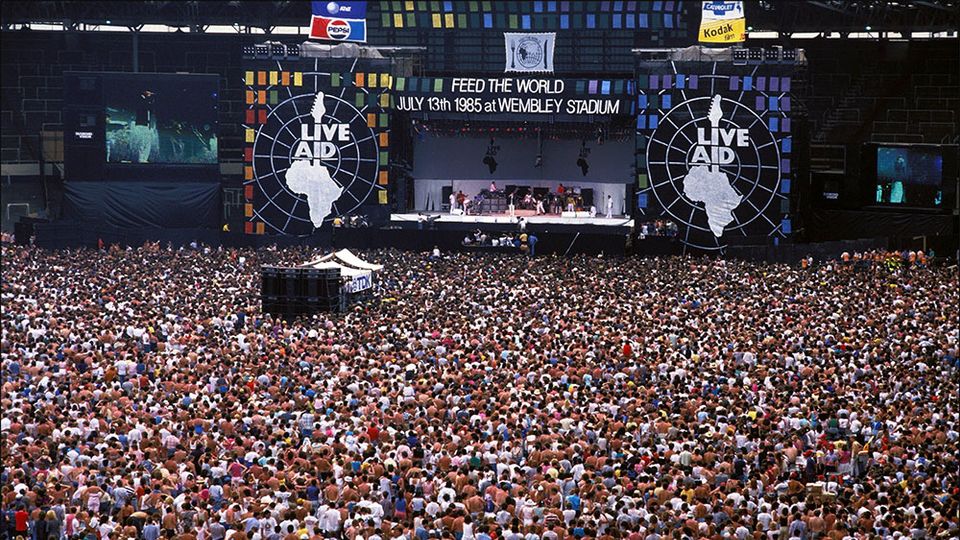

By the late 1980s, almost all of Africa had finally gained independence. But, just because these former colonies had now become free, did not mean there was no poverty, famine, or political strife. Ethiopia had a huge struggle in the 80s, as there was a civil war and a large famine. Many people may know about this because of Live Aid, which was a concert that was made to raise money for Ethiopia’s famine – the same concert that gave us Queen’s most famous live performance. And some African nations remain deeply in poverty, with a debt crisis and government corruption to blame. It seems like we as a society never get over the lasting effects of colonialism, as these African lands were robbed naked by the Europeans, barely giving them any way to rebuild their society. But, Africans’ use of music as a form of expression has never stopped. Kuti’s message can still be felt in the music of Africa today, even if it is less political. Songs like Burna Boy’s “Ye”, which talks about the struggles of being an African musician trying to break through, feels like a Kuiti classic updated for modern times.

In conclusion, the motherland of civilization was robbed naked by decades of colonialism. Then, the colonies started rising up against their European overlords, birthing the era of de-colonialism. And, music like Highlife, and especially Afrobeat, were used as the soundtrack of this era of rising freedom throughout Africa. They were each born of a blend of influences by the colonizers and the colonized, with Afrobeat becoming the true music of the people. By the latter 20th century most of Africa was independent of outside control, but not without hardship economically and politically – and it seems like the effects of colonialism are still there, even today. And just like in the 1970s, Africa’s current musicians carry on the same vision that Fela Kuti had five decades ago of using music as a weapon: informing, protesting, bringing attention to life on the continent, and showcasing both the struggles and joy of its inhabitants.

Leave a comment